Beyond the Snarge: Reporting more than just strikes

This website has been pretty quiet for a long time. And while I would love to say that it is because I’ve been working hard on my PhD research project, it has been more about me just working hard at my day job (which, to be fair, is pretty exciting and challenging). But it feels great to share that I’ve made a little progress of late with the formal publication of my project’s literature review - A Review of Wildlife Strike Reporting in Aviation: Systems, Uses and Standards.

Yes, another academic journal article and with my “spare” time devoted to completing this project, I’ll be making a few changes to this website in line with this renewed focus.

What’s a Literature Review?

In order to qualify for a PhD, you have to show that your research makes a substantial and original contribution to human knowledge. And the first step of showing that your work meets this criteria is to make sure no one else has written about it.

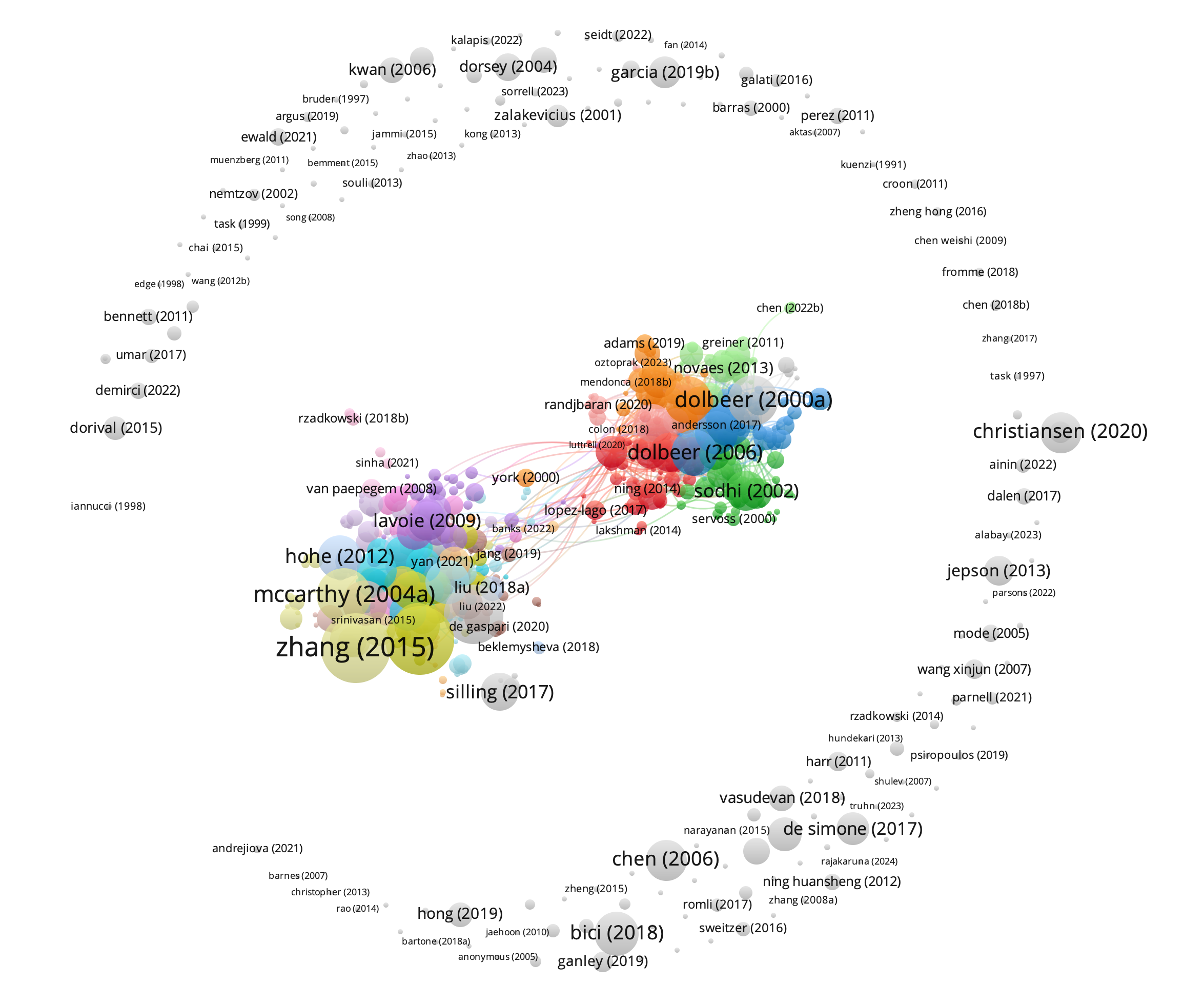

As with everything else in science, you do it in a structured way using refined search criteria and curated, scientific journal databases. You also apply cool analysis techniques like bibliometric analysis and visualisations:

A somewhat galactic view of wildlife strike literature visualised with the help of VOSviewer

What this tool allowed me to do was identify exactly the area within the literature where I would find discussion on wildlife hazard management. It is that colourful glob of papers found on the upper-right side of the twin system at the centre of my literature galaxy.

My Contention

As you no-doubt know, wildlife strikes are among the most commonly reported safety events in aviation. In Australia, they’ve accounted for roughly a third of all safety reports in the last decade. Globally, the estimated annual cost is well into the billions. The industry takes the risk seriously. But are our reporting systems keeping pace with how we now manage these hazards?

That’s the question I’ve explored in my paper, published with the help of my supervisors Steven Leib and Wayne Martin.

More than just strikes

Modern wildlife hazard management isn’t just about counting the number of times a bird collides with an aircraft. We’ve moved to a broader, risk‑based approach: understanding the hazard itself, its context, and the conditions that lead to incidents. Yet the foundational reporting standards, those that shape most national systems, are still based on a 1970s definition of a strike: an actual collision.

This is a bit like trying to manage runway incursions by only counting the ones that resulted in a collision. You miss the rich data from near‑misses, avoidance manoeuvres, and other wildlife‑related events that could tell you how the risk is evolving.

The hidden part of the iceberg

The safety community often talks about the iceberg model: above the waterline are the incidents we see and count; below are the near‑misses, hazards, and warning signs that rarely make it into the stats. For wildlife hazards, the “below the waterline” events might be valuable.

A pilot swerving to avoid a deer, a wasp blocking a pitot tube, a python hitching a ride in the avionics bay—these aren’t hypothetical. They’ve happened, but they’re rarely part of the official dataset unless there’s actual damage.

Without this information, wildlife and safety managers could be caught off‑guard. Strike data alone may not show a change in local conditions until it’s too late.

Why the standards matter

International standards drive national regulations, and those in turn dictate what the industry monitors and reports. ICAO’s current standard requires member states to collect strike reports for the global database, IBIS. And the wording is still anchored to actual collisions, while ICAO guidance documents now talking about “wildlife hazard events” more broadly.

These guidance documents have kept pace with, if not driven, the industry’s approach to wildlife hazard management butchanging that standard isn’t as straight forward. ICAO’s amendment process can take years. Any push for change would do well to have industry consensus first.

Building consensus

This is where my PhD research project comes in. My project and paper proposes using a structured consensus‑building method, the Delphi technique, to get agreement across industry and academia on what types of wildlife-related events should be reported as part of a national reporting system. With a clear, agreed‑upon scope, the case for updating standards becomes much stronger.

In other words: before we can convince ICAO to change the rulebook, we need to get our own house in order.

Why this matters

Better reporting requirements won’t just improve datasets. They’ll give wildlife and safety managers earlier warning of emerging problems, support for more accurate risk assessments, and help avoid unintended consequences, like over‑investing in managing a species that isn’t actually a high‑risk hazard.

It also matters for benchmarking. Right now, differences in national definitions mean comparing data between countries is often an apples‑to‑oranges exercise. A standardised approach could change that.

Looking ahead

Wildlife hazard management has matured into a sophisticated, multi‑disciplinary field. But our reporting standards are still playing catch‑up. My hope is that this paper will add momentum to the industry conversation, and maybe help us see that the most valuable strike data might come from the ones that never happened.